Twelve of us stood patiently in the narrow Bolivian alley. The courtyard nearby was humming with local kids, kicking homemade footballs around, riding rusty bicycles. In brand new outdoor gear and digital SLR’s hanging off most necks, we looked as out of context as a gringo tourist could.

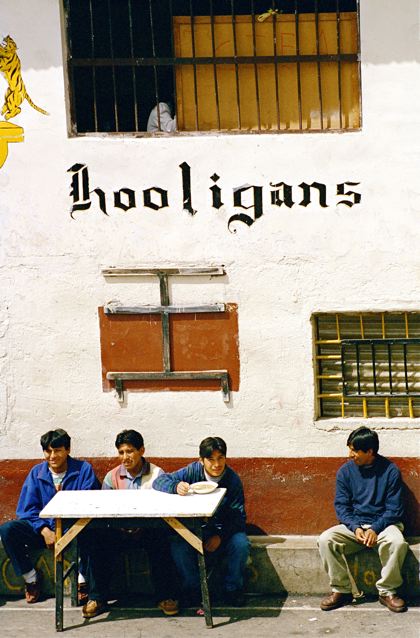

Our wiry resident escort, Luis, kept anxiously turning his head from his visitors to a tightly clenched cigarette butt between his fingers, and then on to some of the more curious locals which started gathering nearby. He stretched a lean finger towards one of the four silent men who circled the group, and kicked off a most unusual sightseeing expedition with his trademark intro: “Inside this prison there’s a hierarchy of the eight strongest and most respected inmates. Your bodyguard Juan here is number two. I’m number six. Welcome to San Pedro Jail.”

By: Max Ribitzky, MOTTO Editor / Photography: Satu Suomela

Welcome to San Pedro Jail, La Paz, Bolivia. A colossal concrete building in the heart of the Bolivian capital, San Pedro looks like a standard penitentiary facility from the outside. And like many other establishments of its kind, most of the 1,500 inhabitants (including a handful of foreign backpackers on an unexpectedly extended stay in Bolivia) are inside for drug trafficking. That is, however, where the similarities to other prisons pretty much end, and the free market system – most curiously – kicks in.

San Pedro correctional facility is a self-sufficient socioeconomic eco-system. Prisoners trade for a living and run the jail, unbothered by the guards, which rarely enter through its front gates. On arrival, the prisoners buy, and are registered as legal owners of, a single cell. They get to keep the key, and can wander freely around the jail at all times. Those who cannot afford the cheapest cells, for 500 dollars, sleep on the kitchen’s floor.

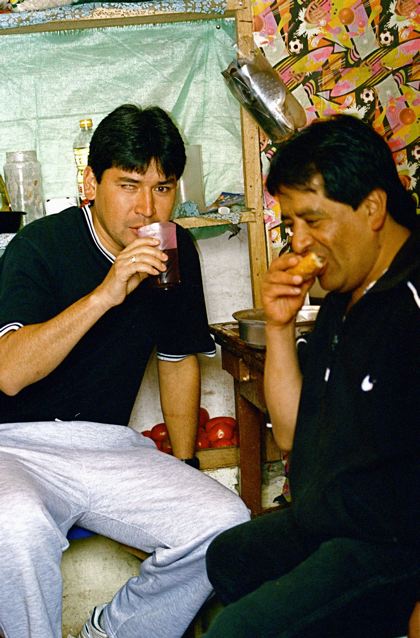

The inhabitants of San-Pedro are kept away from the world, but their world is in there with them. Many have wives and children living in their cells, leaving for work and school outside the prison daily and returning before sunset. Inmates operate small businesses inside San Pedro’s walls: from restaurants, vegetable stalls and make-shift barber shops, to document forging and gambling operations, almost every possible need is catered for inside the big house. Since 2002, thanks to a few entrepreneurial inmates, San-Pedro’s local population of convicts rubs shoulders, three times a day, with small groups of courageous American, Swedish and Japanese holidaymakers who book organized tours of the facility.

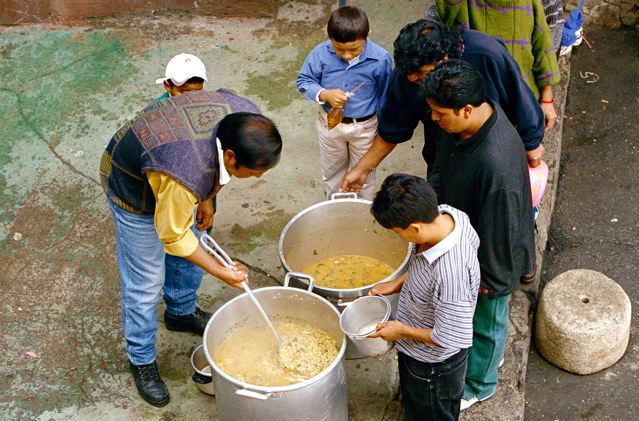

Those who cannot afford the cheapest cells, for 500 dollars, sleep on the kitchen’s floor.

The local godfather controls the inner-jail tourism industry out of his five-star, $12,000 suite, which he equipped with a sauna and a big screen TV with full-service American cable. Under his governance, the entire prison concurs to an independent set of laws and regulations, enforced by some two to three monthly stab-inflicted deaths – or so we are told. The Godfather’s goons escort the tourist groups around San Pedro daily, starting at the prison gates where Luis picks them up. On a cloudy Monday afternoon, after paying seven bucks each, we were led through the main yard, where lunch is being served out of oversized tin cans. “The only thing that’s free in here is the food,” explains Luis. He continues with a dismissive gesture of his hand: “but only the biggest losers eat it. It’s full with tranquilizers. Makes you quiet like a mouse. We don’t touch it.”

Luis leads the group through several narrow passages, winding between the prison’s poorest sections, past a hotel built to accommodate overnight visitors, and a little church with a large Coca-Cola banner on its side wall (the American beverage company had apparently negotiated an exclusivity deal for inner jail distribution of its products, to the exclusion of all competitors.) The next stop on the tour is a viewing of a typical, empty cell, and Luis sends the tourists up a rickety stairway by pairs. Inside the empty cell we are greeted by one of Luis’ associates, who presents us with a few small bags of white powder, of what we are lead to believe is the non-Cola type of Coke, at what he refers to as “the best price in Bolivia.”

When the group finally emerges from the maze of tiny cells and dark hallways, we are ushered onto an open-space football pitch, where some of the inmates and their sons are passionately engaged in discussing the right distance of a football from the goal, for a penalty kick that is about to be taken. Luis points to a man-sized trench in the ground, directly behind the goal post: “This is the hole. If two men have an argument, they solve it there, but with no weapons. Only with the hands. Behind the hole is the stage: when politicians want to convince us to vote for them, they visit San-Pedro and speak to us on this stage.”

This is the hole. If two men have an argument, they solve it there, but with no weapons.

We leave San Pedro at nightfall, ejected back to the unpaved streets of La Paz. Once the centre of the mighty Inca Empire, Bolivia today is plagued with inequality and inadequate development, making it the poorest nation in South America. Almost half the country lives in abject poverty, so it stands to reason that any opportunity for entrepreneurship is eagerly capitalized on. In San Pedro it created a strange and disorienting alternate universe, which nevertheless resulted in unlikely benefits as well, eliminating the heavy economic burden jailed criminals there would have imposed on an already struggling society.